Motorists and moose don’t mix

One winter night in 2010, a young man died when his car struck a moose on U.S. 20 near Thornton. The tragedy graphically underscored the dangers of wildlife, especially big animals, on state highways.

“Driving conditions were less than ideal because of fog,” the Post Register reported Jan. 31, 2010. “Emergency medical services crews were dispatched at 11:36 p.m. [Friday, Jan. 29], but [Derek] Johns, a 24-year-old student at Brigham Young University-Idaho, was pronounced dead at the scene.

“Crews from the Department of Fish and Game were called to remove the moose, which was also killed,” according to the newspaper report.

Crashes involving wildlife in America kill more than 200 people each year and seriously injure thousands more.

The cost of death, personal injury and property damage totals billions of dollars. Many animals also perish.

Transportation departments around the country have addressed this problem by constructing animal overpasses or underpasses to safely convey wildlife over or under roads. But these structures are expensive.

ITD has no animal overpasses, but it boasts five animal underpasses, four on U.S. 95 in north Idaho and one on Idaho 21 northeast of Boise. Effective at passing wildlife, each of the structures costs a minimum of $500,000.

State highway departments also install wildlife-detection systems, which alert motorists to animals present. These devices are less expensive than overpasses or underpasses, but they still cost tens of thousands of dollars and are expensive to maintain.

Automakers recently announced animal-detection systems in upcoming vehicle models, which will warn drivers of large animals in their path.

Road departments concentrate on stretches of highway most frequented by wildlife. It isn’t feasible to construct a bridge or install a detection system wherever an animal may access a route, which is everywhere.

Which brings us to a recent study.

Where oh Where

A few years ago, District 6 Senior Environmental Planner Tim Cramer proposed a study to identify the main animal-crossing locations in Island Park, where wildlife abound. Timing

of this proposal stemmed in part from community residents complaining about too many vehicle-animal collisions and near misses along U.S. 20 in the vicinity.

ITD signed a memorandum of understanding with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), an international organization, in October 2009 to study crossing locations of moose and elk. The consortium determined to identify crossings of U.S. 20 and Idaho 87, which together traverse the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

District 6 Engineer Tom Cole (now retired) alerted Tim to a potential funding opportunity if the environmental planner could quickly draft a scope and budget for the project. The result was $575,000 in financing through the American Restoration and Recovery Act, after which researchers set out to identify not only impacts on U.S. 20 and Idaho 87 of moose and elk crossings but also impacts of U.S. 20 and Idaho 87 on animal movements and habitat.

Teams from IDFG and WCS captured 42 moose and 37 elk, fitting them with radio-transmitter collars for a three-year study of animal and herd movement. Tim designed the environmental and traffic study in collaboration with ecological professionals at IDFG and WCS, and with traffic engineers at ITD.

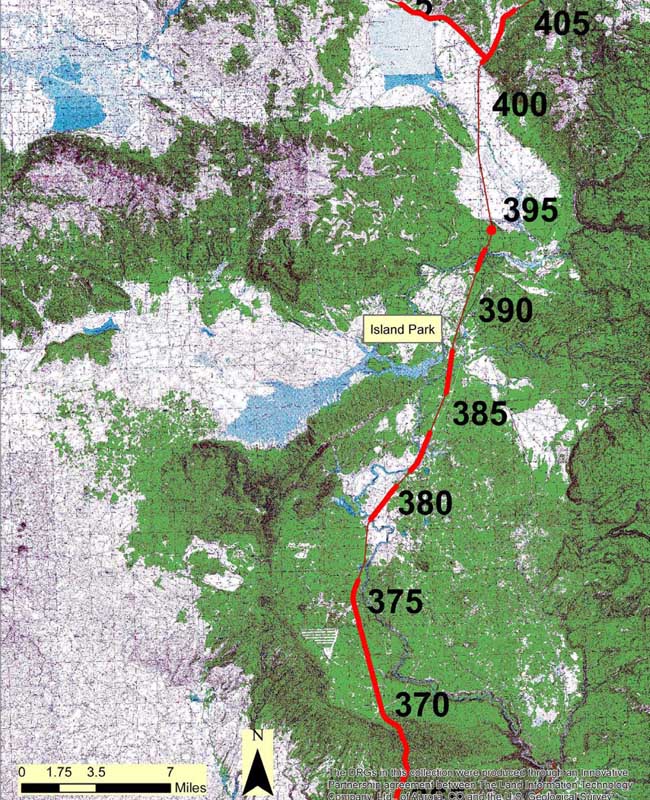

At the conclusion of the research last December, data showed 15 moose crossed U.S. 20 and Idaho 87 fully 354 times, and elk crossed the highways 152 times. Animals mostly accessed nine stretches along U.S. 20 and Idaho 87 (see red bands on map below).

Movin’ Movin’ Movin’

Except for moose that live in the Island Park area year-round, moose and elk populations migrate between the Island Park region and winter ranges on the East Snake River Plain near St. Anthony.

Learning of the study, National Geographic Television shot footage of research teams trapping and collaring moose and elk. Footage appeared in the documentary “Wild,” which aired in 2011.

After analyzing the data, officials of WCS suggested to ITD leaders that state traffic engineers consider a combination of overpasses/underpasses, detection systems, warning signs and roadside clearances to help reduce vehicle-wildlife collisions throughout eastern Idaho.

District 6 plans to define a path forward next year. For now, the sign crew will post additional wildlife crossing signs at migration points.

Regardless of the strategies selected, drivers must remain alert. Wild animals are ever unpredictable, as evidenced by the Thornton incident. They emerge anywhere, anytime, just when you least expect it.

In the near future, District 6 hopes to help eliminate a good portion of that ambiguity.

Moose and elk frequently accessed nine stretches of the two highways in the Island Park area (see red bands). The eighth and ninth bands at the bottom run together. The black numbers along the routes are mileposts. Senior Environmental Planner Tim Cramer of District 6 says: “Highways and associated traffic impact wildlife in four ways: decrease the extent and quality of habitat, limit access to resources, sever migration routes, and fragment populations, increasing wild animal vulnerability.”

Published 11-07-14