Deep Thoughts: Zarate, Gordon ponder bridge over Clearwater River

ITD finishes successful project under budget and ahead of time.

How would ITD save a critical bridge over the Clearwater River in Lewiston while also enhancing fish habitat? Over the course of 29 days early this fall, that's the question ITD Engineer-in-Training Janet Zarate needed to answer.

The majestic Clearwater is a 75-mile-long river flowing west from the Bitterroot Mountains at the Idaho-Montana border until it converges with the Snake River at Lewiston. It passes through four of the five counties in north-central Idaho (ITD's District 2) and is the largest tributary of the Snake.

The recent bridge project in District 2 was a unique effort to combat scour (erosion) around the Spalding bridge’s piers. It also provided the perfect project for Zarate to hone her engineering skills.

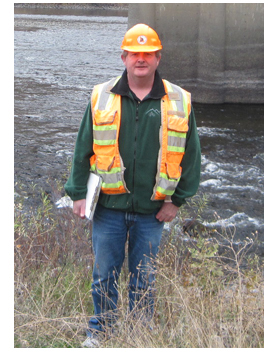

Zarate (pronounced like "karate”), now on the district’s project development team, is currently designing left-turn bays and right-turn lanes for a project on Idaho 8. She is completing environmental documents, right-of-way plans and other measures. Until recently, Zarate and Robert Gordon were the project coordinators wrapping up ITD's construction following West Company’s completion of the Spalding Bridge (Clearwater River Bridge) project under budget and ahead of schedule.

The concrete-deck, steel-girder bridge was built in 1962, is more than 1,200 feet long, and approximately 33 feet wide.

The project was completed at approximately four percent under the original contract amount, and was finished 14 days ahead of the Sept. 30 deadline.

Zarate was both inspector and co-manager on the Spalding Bridge project. In addition to ensuring compliance with federal-aid labor requirements and Tribal Employment Rights Ordinances — half of the six-person work crew was from the Nez Perce Tribe — she also was instrumental in maintaining compliance with the U.S. EPA Clean Water Act Section 401 permit.

UNIQUE CHALLENGES

The project had unique challenges from the beginning. The bridge spans the Clearwater, a body of water vital to the area’s recreation and commerce, so minimizing impact to the river was critical. The bridge was one of the state’s 10 most scour-critical bridges — at risk of failure due to erosion — so repairs could not wait.

At its worst point, scour had undermined a section estimated to be a foot deep and 4 feet by 8 feet in dimension. Dan Gorley of ITD’s Headquarters’ Bridge Asset Management team anticipates that the sufficiency rating of the bridge will rise significantly pending a bridge inspection next spring.

The project was complex, requiring ingenuity. The Project Development staff in District 2 stepped up to the challenge. The main concerns addressed in design were constructability and reducing the effects of construction on endangered fish such as bull trout, Snake River Basin steelhead and Snake River fall Chinook salmon.

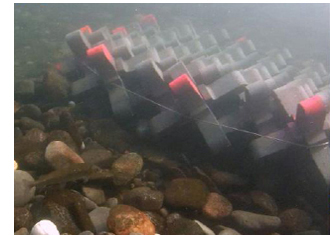

Also unique were the nearly 2,700 lbs. of articulated riprap per mat placed at the river’s bottom to shield the piers against further erosion from water flow at the pier. After work was done, nearly 400 of the heavy concrete A-Jacks mats were placed on the riverbed to continue to provide armor against erosion. Research indicates that voids in the mats provide a support system for the river gravels and help to promote fish habitat. The mats, made of more than 30 individual units, were secured with corrosion-resistant steel cables.

Several different options for construction were investigated. Lowering the bundles from the Spalding bridge deck would have impacted the flow of traffic on the narrow bridge. After numerous discussions with barge suppliers, ITD District 2 staff determined that using a light-duty barge would be a feasible option for transporting the heavy A-Jacks bundles.

“This is the only project that I am aware of in about the past 10 years in this area that did not affect the flow of traffic in some way,” said Curtis Arnzen, District 2 project development engineer. The project had a mobility-focused design that maintained an open roadway for commuting, commerce, recreation, and tourism.

Approximately 5,700 vehicles cross the bridge each day.

Collaboration with participating agencies was vital to the project's ultimate success. During the course of the project, ITD worked with the Coast Guard, Nez Perce Tribe, Idaho Fish & Game, Environmental Protection Agency, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and U.S. Fish & Wildlife service (USFWS).

“Communication was key,” Arnzen said. “The permitting agencies responsible for the endangered fish were very good to work with, understood the urgency of the project and helped the project to succeed.”

District 2’s design team of Arnzen, Grant Hogg and Shawn Smith worked with outside agencies to establish timing for the project.

The contractor was only allowed to start once the flow rate of the Clearwater River had reached 25,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) and falling. Work began Aug. 4. Twenty-nine days later, the project wrapped up. This allowed the contractor to have all equipment removed from the site so as not to interfere with the river’s catch-and-keep fishing season. This was especially important to anglers who started camping out in September in anticipation of an expected record Steelhead run this year.

Although the A-Jacks articulated riprap approach was not the first use of the technology — ITD used it in 2002 on the Tilden Bridge in Blackfoot and on the Snake River Bridge west of Shelley, and also on the Carmen Bridge on the Salmon River last year — it was the first time it was used in a fast-moving water situation and to this magnitude.

More than 14,000 individual A-Jacks units were proposed. This dynamic created a unique set of challenges. First, a diver typically provides real-time guidance for successful placement of the A-Jacks mats, according to Joe Schacher, the resident engineer on the project.

“In our case, the water was too swift to safely allow a diver to be involved,” he said. “We met with the A-Jacks supplier/manufacturer early on and received insight into how the units react to the river morphology to successfully armor the piers.”

Schacher said that since the majority of work could not be visibly inspected during placement, the contractor tried different underwater video products such as an ice-fishing camera and a GoPro camera, to provide visual assurance of proper placement.

"They finally settled on tying a waterproof GoPro camera to a length of one-half inch rebar, which allowed it to be steady enough for inspection and also mobile enough to reach even the deepest sections."

ITD also used other advances in technology to assist in the river work. The project team visually recorded the work progress from three vantage points: underwater (the GoPro on a stick); land-based photography – time-lapsed pictures by Zarate; and aerial photography from Joe Schacher's Phanton Vision 2 Quadcopter. Schacher is also an amateur pilot.

Another significant obstacle was changing river conditions. When the contractor began work, the river was running at more than 12,900 cfs and the flow direction turned crosswise to six of the seven piers, making it very difficult to place the barge and equipment.

Zarate said the high volume and discharge rate of the river led to formidable safety challenges navigating the barge and placing mats. In addition, for approximately a week, the flow dropped rapidly to 7,980 cfs, which restricted the barge from accessing the piers downriver when the dropping water level exposed gravel bars below the bridge and caused concerns that areas of the river would become inaccessible to the barge and tugboat.

The contractor and ITD found innovative methods to efficiently place the mats while maintaining public access for boaters. With each issue, the teams met to discuss procedures.

“It was unique, complex and ultimately, a very successful project," Zarate said. "It met our needs, and most importantly, the needs of the users — the citizens of this part of the state," she explained.

ZARATE EXPERIENCE

“It is important to recognize the efforts of ITD and district staff in Project Development, Environmental, Materials, and Bridge throughout the process. “I am very appreciative of all their hard work to create this successful project,” said Zarate.

“This was my first summer working in District 2’s Residency. I am very thankful for the opportunity to work with such a great team on this project,” she added.

“I benefited greatly from the guidance of seasoned professionals in District 2. The mentorship of Robert Gordon, who has more than 25 years of experience with ITD, was invaluable to learn the skills needed to have a successful construction season,” Zarate explained.

“I was impressed with the concerted effort to develop solutions for the issues encountered during the execution of this project.”

“Janet was involved in all phases of the construction process, beginning with the preconstruction meeting and concluding with the finalizing of the project files,” said Gordon. Zarate performed daily inspections, dealt with environmental issues, and completed required project documentation. She also maintained a good working relationship with the contractor, which made it more of a team effort and allowed quick resolution of issues that came up during the project.

“The Spalding Bridge Scour mitigation project using A-Jacks was unique in that much of the work was in fast, deep water,” explained Schacher. Most inspections were done remotely via underwater camera shots after the placements. It was a good lesson in thinking outside of our traditional boxes. The project was successful mainly due to the team effort provided by ITD and the contractor.”

Pictured above: top left is Zarate; top right is Gordon; below them are side-by-side images of the A-Jacks mats bundled on land and deployed underwater; and immediately above are pictures of the barge moving into position and work being performed from the barge.

Published 11-21-14