ITD past and present: Battle-tested, resolute

Disasters 20 years ago this winter showed agency's mettle

A look to the past often provides a glimpse into the future. For the Idaho Transportation Department, that glimpse is reassuring, and emergency preparedness remains a core value for the agency.

"It's critical that we show leadership and accountability in securing our transportation system," said ITD Director Brian Ness. "Nothing can bring a government agency to its knees faster than not being prepared to respond. Even though we are more than 14 years past 9/11 and a decade since Hurricane Katrina, we have to always remain vigilant in preparing for emergencies." Since 2011, Ness has been chairman of the Special Committee on Transportation Security and Emergency Management for the organization guiding all state departments of transportation.

Twenty years ago this winter, Mother Nature unleashed one natural disaster after the next, all over Idaho. The results severely tested the resolve of the department and Idahoans. The onslaught was fierce. ITD battled back.

First, late in 1995, came a landslide in District 2 (north-central Idaho). Then came a blizzard in District 5 (southeastern Idaho) and District 6 (eastern Idaho) in January 1996. Most damaging of all was extensive flooding in District 1 (northern Idaho) a month later, fueled by warm temperatures and rain.

Traditional “job descriptions" were tossed aside as other ITD sections and districts quickly became involved in the effort. Cooperation was the name of the game.

Holiday challenge

The outstanding efforts of that winter began with the response in late November 1995 with the U.S 12 slide. Crews spent long hours and devoted extra labor to reopen the highway as the holidays approached. The closure was a major inconvenience to travelers, who were eager for the highway to be passable.

The time and dedication given to reopening the highway by Christmas was undoubtedly appreciated by the public.

The route reopened Dec. 23, just 25 days after the first washout stemming from Noseeum Creek, a tributary of the Lochsa River. Torrential rains, landslides and blocked culverts overwhelmed the small creek, causing a massive washout and dumping tons of water and debris across the road. The river eventually covered the highway for nearly a half-mile upstream.

All-out battle

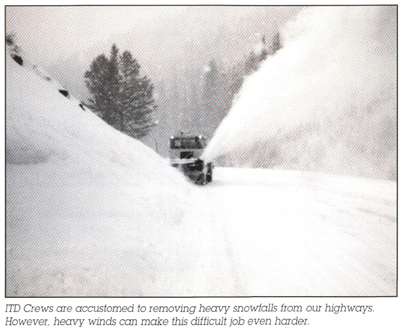

Following closely on the heels of that disaster came the blizzard in districts 5 and 6 in late January 1996. Again, staff worked tirelessly and put in additional time to dig out the many roads closed by the whiteout conditions. While snowstorms do not cause the long-term damage to highways that floodwaters do, they can shut them down just as fast and tax the personnel and resources of the crews charged with keeping them clear.

Extremely high winds turned a heavy snowfall into an all-out battle to keep those districts' roads open, including many employees not normally assigned to snow removal.

On Jan. 26, a storm began to roll across the state, lasting through the weekend, and depositing up to 12 inches of snow on the ground. However, the real challenge was the wind. Many areas experienced sustained winds of 30-40 mph and gusts up to 70 mph. Crews from the two districts used 4,500 hours of labor (anyone and everyone was used) and more than 25,000 gallons of fuel. The winds caused nine-foot-high drifts and zero visibility, essentially closing almost every road in southeast Idaho at one point.

“There was about a 10-day period where our plows never stopped — they worked 24/7 and we emptied out the office spaces to drive some of the shifts,” said Ed Bala, who is now the district engineer in southeast Idaho but was then a resident engineer in the Rigby office.

“I remember lots of stories of digging cars and trucks out of the big drifts on U.S. 20 west of Idaho Falls,” Bala recalled.

Rising tide

In February 1996, it was northern Idaho's turn. Department personnel worked 24 hours a day, on weekends, and some used personal equipment to clean up, repair and reopen the highways damaged by flooding. The damage in districts 1 and 2 extended far beyond the state highway system, as did the assistance ITD staff provided. Services and support were stretched thin, beyond the realms of our transportation system, and crews routinely performed in a capacity above and beyond the call of duty.

In District 1, the trouble began Feb 7. Water levels began rising as the snow quickly melted and the rain continued to fall. By the next day, serious flooding had begun, and district personnel sprang into action. Anyone with flagging certification was pressed into service. Typical job functions became non-existent as the concept of “other duties as assigned” came into play.

Thanks to a quick response, many roads were kept open to traffic. Fourth of July Pass was in danger of losing both westbound lanes at one point. Maintenance crews quickly cleared debris and diverted runoff water. Repairs were then made to the road surface and subgrade, keeping traffic flowing on Interstate 90.

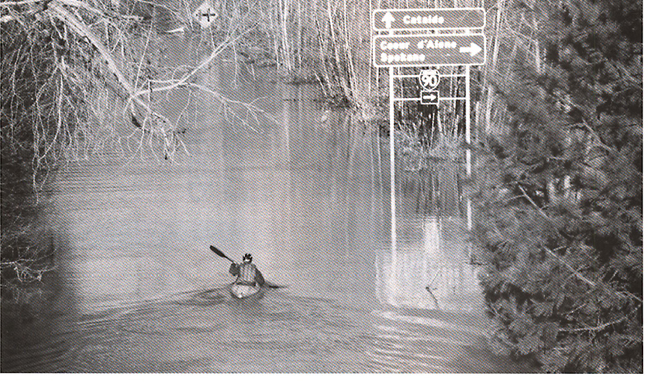

Other highways did not fair as well. In Bonner County, torrential rains caused enormous amounts of runoff to pool across U.S. 2 at Dover. Nearly four feet of standing water covered the road, overwhelming the drainage capabilities of the highway.

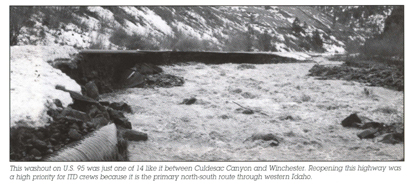

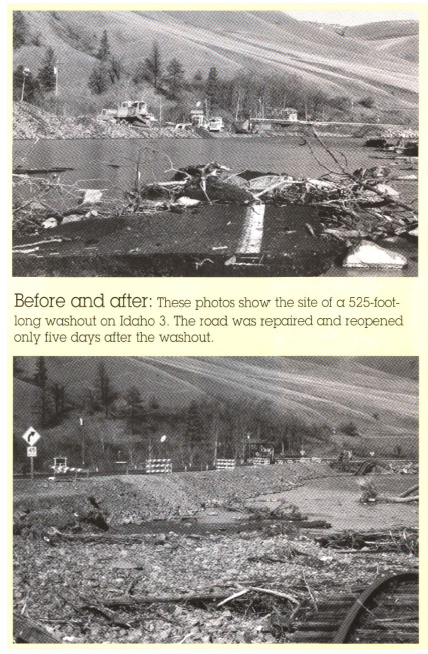

Perhaps the hardest hit area was St. Maries. The St. Joe River rose so fast that it breached the dikes, covering Idaho 3 and flooding most of the area north of town. At one point, the highway was under more than 20 feet of water. While the dikes did not hold, the railroad bed along the highway did, acting as a dike to keep the water from draining off the highway. A 525-foot-long, 12-foot-deep section of Idaho 3 washed away.

Partners pulling together

Then-District Engineer Tom Baker spent most of the day Feb. 10 on the phone with local officials and representatives from Burlington-Northern and Union Pacific railroads to help get the water off the highway.

A deal was made with the railroads and they tore out their own track and cut a trench in the track ballast, allowing tens of thousands of gallons of water to drain off the road --taking themselves out of business for a short time in the process.

The district also worked closely with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to repair the dikes and Idaho 3 was opened to traffic. Huge pumps operated on a 24-hour basis to drain St. Maries.

“We actually were declared a disaster area,” recalls Scotty Fellom, who was at that time the district’s Supply Operations supervisor and is now D1’s administrative manager. “It enabled us to get special funding to assist with the cleanup and stabilization. We even flew in a special soils and terrain specialist from Colorado.”

In total, there were 22 closures on 13 different state routes. One week later, there were only four. By late February, there were none.

Scott Stokes, now ITD’s deputy chief, had just been promoted to district engineer overseeing the northern Idaho region.

“My first day on the job was a tour of the district. Water was over I-90 in Cataldo, SH 3 was washed out in St. Maries, and U.S. 2 had turned to mud west of Sandpoint. It was a district-wide mess. But thanks to the work and experience of the field people, we were well taken care of very quickly. It was very stressful during the heat of the battle, but the crews were awesome. There’s no question I was impressed with the way the district pulled together to solve the crisis.”

New solution to an old problem

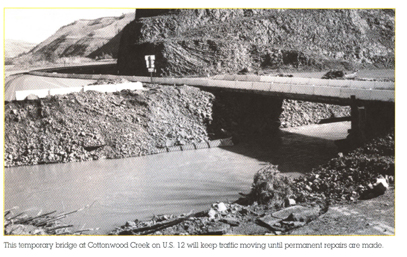

In District 2, an old solution solved the new problem of a washed-out bridge.

When floodwater collapsed the multiplate-arch bridge on U.S. 12 at Cottonwood Creek, a temporary bridge utilizing flatbed railroad cars was used just south of the missing bridge to carry traffic. This allowed District 2 to maintain travel on this crucial commercial route.

U.S 12 was a flood-repair priority project for District 2 because of the number of vehicles that travel the route. Maintenance crews were fortunate because there already were concrete abutments in place at the temporary bridge construction site, reported then-District Engineer Jim Carpenter at the time.

Using flatbed railroad cars as a temporary bridge base wasn’t a new innovation for District 2. The district had used the cars in five other projects since 1987 to construct temporary bridges during scheduled construction projects. But this was the first time the cars had been used in an emergency situation, Carpenter said.

Using the flatbed car system was the quickest way of getting the route reopened. The district considered moving a portable bridge to the site, but the need for additional abutment work would have postponed any opening for at least another week.

That would have forced motorists to continue to endure a one-way, two-hour detour route.

Carpenter, who is now ITD’s chief operations officer, said the idea worked. “The bridge stayed in place for some several months without any complications. Matt Farrar (now ITD’s state bridge engineer) did a lot of the bridge work on this and was instrumental in developing the plan.”

“Thank you does not adequately express our appreciation. Each of you truly makes ITD a model and exemplary agency,” the Idaho Transportation Board said at the time.

"As tragic as these events were, I am extremely pleased with the way our District 1 and 2 forces pulled together and rose to the challenge. All of us should be very proud of their efforts and accomplishments," then-Chief Engineer Jimmy Ross told lTD employees.

Resolve

ITD had barely caught its breath from these events when the agency was thrust right back into the fray.

In mid-November 1996, winter hit with a vengeance in northern Idaho in what is known as lce Storm '96. Snow and rain, frequent freezing and thawing cycles, and the water-saturated roadway base took their toll on road surfaces. More than two feet of snow fell in a 24-hour period. With so much snow, the water-soaked ground began to give way, causing numerous mudslides on U.S. 95, Idaho 57, Idaho 97 and other area highways.

The following June, the Snake River broke over its banks all over southeast Idaho – washing out bridges, levees, and many acres of farmland. Disastrous spring flooding occurred on the Snake River in eastern Idaho from March 14 to June 30, 1997, primarily due to the rapid melt of a record-high snowpack at high elevations, and heavy rains in late May and early June, prompting a federal disaster declaration for eight counties. Interstate 15 was closed for nearly 20 miles between Shelley and Blackfoot. About 50,000 acres were affected by the eastern Idaho floods.

Around that same time, in 1997, a mudslide hit Bonners Ferry near the golf course with a wall of mud 6 to 10 feet deep that hit one car broadside and moved it 100 yards down the course. The driver, despite serious injuries, crawled out of the car and back to the highway through the thick mess to flag down help.

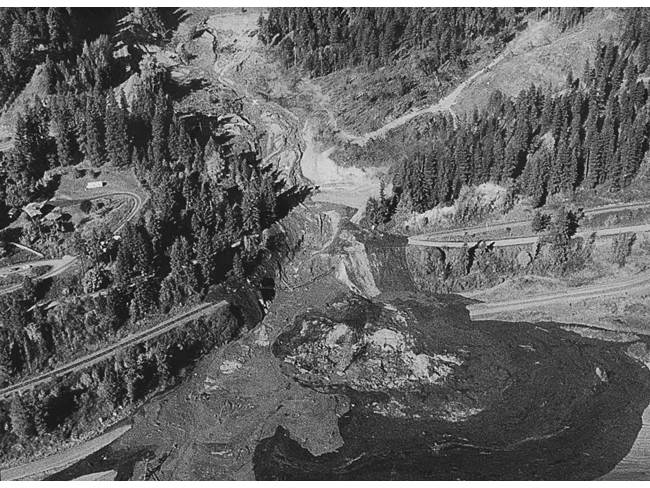

Then came the Bonners Ferry landslide in 1998 (pictured directly above), which closed U.S. 95 for 13 days. Again, teamwork was the key. "Teamwork is the formula to success…teamwork internally and teamwork with our external partners," said Stokes. "If you don't have a good relationship with your local government leaders and other stakeholders, it gets tough."

This proves that the next disaster may be just around the corner, but when it arrives, ITD will again be ready.

Published 01-29-16